Discussion Guide

for the Consultations on the Board's Excessive Price Guidelines

Released May 2006

Purpose:

To obtain written feedback on specific elements of the Guidelines used to determine whether the prices of patented medicines are excessive, including ideas on possible options for change.

Table Of Contents

- Overview of the PMPRB

- Excessive Price Factors in the Patent Act

- The Excessive Price Guidelines

- Events Leading to the Current Consultations on the Guidelines

- Purpose of the Discussion Guide

- Issue for Discussion

- Issue 1 Is the current approach to the categorization of new

- Issue 2 Is the current approach used to review the introductory prices of new patented medicines appropriate?

- Issue 3 Should the Board’s Guidelines address the direction in the Patent Act to consider “any market”?

- Annex A - Development of the Guidelines

- The Excessive Price Guidelines, 1988

- Drug Categories and Associated Price Tests

- Response of Stakeholders

- Revisions to the Guidelines, 1993

- The Road Map for the Next Decade, 1999

- The Working Group on Price Review Issues, 1999-2002

- Conclusion

- Annex B - The Patented Price Review Process

Overview of the PMPRB

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is a federal independent quasi-judicial body established in 1987 under the Patent Act (Act). The Minister of Health is responsible for the pharmaceutical provisions of the Act as set out in sections 79 to 103.

Although the PMPRB is part of the Health Portfolio, it carries out its mandate at arm's-length from the Minister of Health.1 It also operates independently of other bodies such as Health Canada, which approves drugs for safety, quality and efficacy, and the public drug plans, which approve the listing of drugs on their respective formularies and reim-bursement for eligible beneficiaries.

The PMPRB has a dual role:

Regulatory – To protect consumers and contribute to Canadian health care by ensuring that prices charged in Canada by manufacturers for patented medicines are not excessive;

Reporting – To contribute to informed decisions and policy making, by reporting on pharmaceutical trends and on the R&D spending by pharmaceutical patentees.

In its regulatory capacity, the PMPRB is responsible for ensuring that the prices patentees charge wholesalers, hospitals, pharmacies and others for prescription and non-prescription patented drugs sold in Canada are not excessive.

The Patent Act does not define what constitutes excessive; however, it does list the factors that the Board shall take into consideration in determining whether a price is excessive.

1 The Health Portfolio contributes to specific dimensions of improving the health of Canadians. It comprises Health Canada and five agencies, the Assisted Human Reproduction Agency of Canada, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Hazardous Materials Information Review Commission, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board and the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Excessive Price Factors in the Patent Act

85. (1) In determining under section 83 whether a medicine is being or has been sold at an excessive price in any market in Canada, the Board shall take into consideration the following factors, to the extent that information on the factors is available to the Board:

- the price at which the medicine has been sold in the relevant market;

- the prices at which other medicines in the same therapeutic class have been sold in the relevant market;

- the prices at which the medicine and other medicines in the same therapeutic class have been sold in countries other than Canada;

- changes in the Consumer Price Index; and e) such other factors as may be specified in any regulations made for the purposes of this subsection.

85. (2) Where, after taking into consideration the factors referred to in subsection (1), the Board is unable to determine whether the medicine is being sold in any market in Canada at an excessive price, the Board may take into consideration the following factors:

- the cost of making and marketing the medicines; and

- such other factors as may be specified in any regulations made for the pur-poses of this subsection or as are, in the opinion of the Board, relevant in the circumstances.

While designating the factors to be considered, the Act gives the Board significant latitude to determine how these factors will be applied.

96. (4) Subject to subsection (5), the Board may issue guidelines with respect to any matter within its jurisdiction but such guidelines are not binding on the Board or any patentee.

96. (5) Before the Board issues any guidelines, it shall consult with the Minister, the provincial ministers of the Crown responsible for health and such representatives of consumer groups and representatives of the pharmaceutical industry as the Minister may designate for the purpose.

The Board developed the Excessive Price Guidelines (Guidelines) in consultation with its stakeholders, including provincial and territorial Ministers of Health, consumer groups, the pharmaceutical industry and others. The Guidelines provide transparent predictable guidance to patentees on the approach Board Staff uses when determining whether prices of patented medicines are excessive. Having applied the Guidelines, when Board Staff concludes that a price is excessive it conducts an investigation. An investigation could result in: a finding that the price is not excessive; a Voluntary Compliance Undertaking (VCU) by the patentee to reduce the price and pay back any excess revenues earned while the drug was priced excessively or a recommendation to the Chairperson that a public hearing is in the public interest.

Even though the Guidelines are not binding on the Board, in its recent decision in the matter of the price of the psoriasis medicine Dovobet, the Board said it considers the Guidelines an articulation of the methodology used in applying the factors in the Patent Act.2

2 Decision: PMPRB-04-D2-DOVOBET, April 19, 2006

The Excessive Price Guidelines

In summary the Guidelines provide that:

- prices for most new patented drugs are limited such that the cost of therapy for the new drug does not exceed the highest cost of therapy for existing drugs used in Canada to treat the same disease;

- prices of breakthrough patented drugs and those that bring a substantial improvement are generally limited to the median of the prices charged for the same drug in other industrialized countries listed in the Patented Medicines Regulations (Regulations): France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States;

- price increases for existing patented medicines are limited to changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI); and

- the price of a patented drug in Canada may, at no time, exceed the highest price for the same drug in the foreign countries listed in the Regulations.

Detailed information on the Excessive Price Guidelines can be found in the Compendium of Guidelines, Policies and Procedures posted on the PMPRB Web site: www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca, under Legislation, Regulations and Guidelines. For information on the development of the Board's Guidelines see ANNEX A.

For an overview of the price review process for patented medicines see ANNEX B.

Events Leading to the Current Consultations on the Guidelines

The Discussion Paper on Price Increases, 2005

During 2004, the PMPRB was advised that manufacturers of a significant number of patented medicines had informed customers of proposed price increases. The reports of price increases raised questions about whether or not Canada could be on the verge of experiencing a major shift in pricing, bringing the past decade of price stability to an end and adding to pressures on the sustainability of Canada´s health care system and Canadians' ability to afford the drugs they need. In view of these reports, the Board released a Discussion Paper in March 2005 to engage stakeholders in a dialogue and solicit their views on the issue of price increases for existing patented drugs. The Board received a number of stakeholder submissions in response to its Discussion Paper.

As reported in the July 2005 issue of the NEWSletter, the resulting consultation process indicated that price increases are not stakeholders' prime concern. However, stakeholders raised a number of issues concerning, among other things, the factors specified in the Act and the continued appropriateness and relevance of the current Guidelines.

Some stakeholders suggested additional factors that the Board should consider in its review of maximum non-excessive prices such as: the post-market effectiveness of the drug in the real world; linking allowable price increases to the amount of R&D spending the patentee undertakes in Canada; and/or factoring the cost of marketing into how much prices could increase. Any change to the factors used to determine whether a price is excessive would require legislative or regulatory amendments and therefore, more properly reside with the Minister of Health. As a result, the Board is not pursuing these suggestions.

In addition, stakeholders raised a number of complex issues related directly to the price review process, including:

- the possible development of new categories to acknowledge incremental innovation;

- the role of introductory prices as a cost driver; and

- price variations across markets in Canada.

Following a review of the submissions, the Board requested Board Staff to conduct further analyses on these three issues. The Board believes these analyses will assist stakeholders in their consideration of whether changes should be made to the Guidelines and if so what these changes should be.

In the spring of 2006, the PMPRB is beginning a major review of the Guidelines that will include a multi-stage consultation process. The objectives are two fold:

- Build on the knowledge of past consultations, and elicit discussion on the following three key issues:

- The appropriateness of the current categorization of new patented medicines;

- The appropriateness of the current introductory price tests; and

- The significance of price variation across markets.

- Seek targeted input from key stakeholders on options for possible changes to the Board's guidelines, should they be required.

This Discussion Guide marks the beginning of formal consultations as the Board considers the possibility of changes to its Guidelines. Future stages in the consultations will include by invitation, face-to-face meetings with consumers, F/P/T governments, the pharmaceutical industry and others to help debate and refine possible options for amendments to the Guidelines.

Purpose of the Discussion Guide

The Discussion Guide is designed to obtain written feedback on specific Guideline issues, ascertain the need and the support for changes to the Guidelines, as well as views on possible options for changes. The three specific Guideline issues are as follows:

- the appropriateness of the current approach to the categorization of new patented medicines;

- the appropriateness of the current approach used to review the introductory prices of new patented medicines; and

- whether the Board´s Guidelines should address the direction in the Patent Act to consider “any market.”

At this time, the Board has no set position on whether or not changes need to be made to the Guidelines. The written submissions in response to this Discussion Guide will be considered in determining what changes, if any, need to be made. If changes are necessary, the submissions will assist in developing the options for changes. The options will be the subject of future consultations with stakeholders.

Comments on the issues in the Discussion Guide should be forwarded to Sylvie Dupont, Secretary of the Board, no later than August 25, 2006, at the following address:

Box L40

Standard Life Centre

333 Laurier Avenue West

Suite 1400

Ottawa, Ontario

K1P 1C1; or

By fax: (613) 952-7626; or

By e-mail: sdupont@pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca

Issue for Discussion

Issue 1 Is the current approach to the categorization of new

Context:

The price review process for new drugs begins with a scientific review. The current Excessive Price Guidelines (Guidelines) establish three categories for new patented drug products for purposes of introductory price reviews (ref. The Compendium of Guidelines, Policies and Procedures, Chapter 1, Excessive Price Guidelines: para 3.2, p. 9).

Category 1 drug products are a new strength (e.g., 50 mg v. 100 mg) or a new dosage form (e.g., tablet v. capsule) of an existing medicine (sometimes referred to by stakeholders as line extensions).

Category 2 drug products provide a breakthrough or substantial improvement over existing medicines.

Category 3 drug products provide moderate, little or no therapeutic advantage over comparable med-icines (sometimes referred to by stakeholders as “me too” drugs).

All new active substances (NAS) are referred to the Human Drug Advisory Panel (HDAP) for a recommendation as to the appropriate categorization and comparator medicines and appropriate dosage regimens, if any. The HDAP recommendations are based on information provided by the patentee, publicly available scientific literature collected and summarized by a recognized Drug Information Centre and Board Staff, the individual expertise of each panel member and any other information collected by panel members themselves. The price of the medicine is not a factor taken into consideration.

All NASs are either a Category 2 or a Category 3 drug product because Category 1 drug products are a new strength or new dosage form of an existing medicine.

In order to be classified as a category 2 medicine, the Guidelines specify the threshold of evidence required. More specifically the Guidelines state:

A breakthrough drug product is the first one to be sold in Canada that effectively treats a particular illness or effectively addresses a particular indication.

A substantial improvement is one that, relative to other drug products sold in Canada, provides substantial improvement in therapeutic effects (such as increased efficacy or major reductions in dangerous adverse reactions) or provides significant savings to the Canadian health care system.

Health Canada gives each strength of each new medicine a unique Drug Identification Number (DIN). Some new medicines may be available in only one strength, while others may have several strengths, thus multiple DINs.

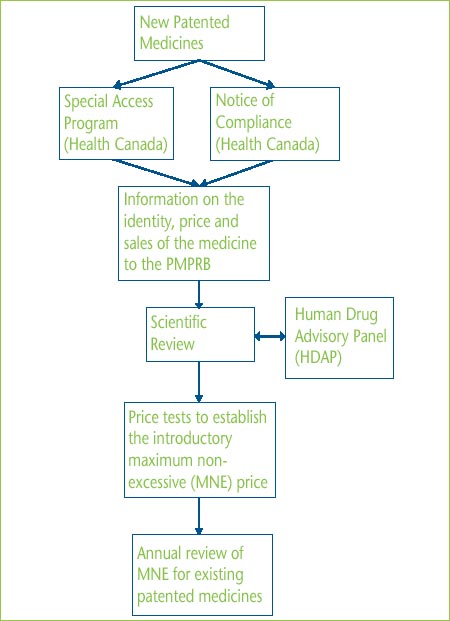

Figure 1 shows the categorization of the DINs introduced in each of the years from 1999 to 2004. For example, in 2004 there were 40 new category 3 DINs (representing 23 new drugs) and 42 new category 1 DINs, while in 2003 there were two new breakthrough DINs (representing one new drug).

Figure 1: New DINs by Category: 1999-2004

Note: This chart includes all new DINs whose introductory prices were reviewed and found to be within the Guidelines.

|

Question 1:

Are the new patented drug categories and their definitions appropriate?

Question 2:

Is it important to distinguish a medicine that offers “moderate therapeutic improvement” from a medicine that provides “little or no therapeutic improvement?” If yes, why is it important? If not, why not?

Question 3:

If the answer to question 2 above is yes, on what basis would a new medicine that offers “moderate therapeutic improvement” be distinguished from a new medicine that provides “little or no therapeutic improvement”?

|

Issue 2 Is the current approach used to review the introductory prices of new patented medicines appropriate?

Context:

The Board, in consultation with stakeholders, developed various tests to determine whether the price of a patented drug product is within its Guidelines (i.e., not excessive). Board Staff applies these tests to the average Canadian price of a new patented drug product (also referred to as the average transaction price).

The Reasonable Relationship (RR) test is used for Category 1 drugs and considers the association between the price of the new strength of the existing medicine and the prices of other strengths of the same medicine in the same or comparable dosage forms.3 The introductory price is considered excessive if it does not bear a reasonable relationship to the average Canadian price of the other strengths of the medicine. In most cases, the reasonable relationship test is sufficient to define a maximum non-excessive (MNE) introductory price for a category 1 new patented drug product.

When the new drug has a different therapeutic use or its dosage regimen is different from the existing medicine the therapeutic class comparison test is used.

The Therapeutic Class Comparison (TCC) test compares the price of the new patented drug product to the prices of other clinically equivalent drug products used to treat the same disease, and sold in the same markets at a price that the Board considers not to be excessive. The price comparisons are made in terms of the price per day or price per course of treatment whichever is more appropriate. Generally the price per course of treatment is used for acute indications and the price per day is used for chronic situations. The therapeutic comparators used are those identified by the HDAP. This test is used for category 3 drugs, and in some cases for category 1 drugs (non-comparable dosage forms).

In the context of a TCC test, the price of a new medicine is considered excessive if it exceeds the highest price of the therapeutically comparable drugs in Canada.

The International Price Comparison (IPC) test com-pares the average transaction price of the new patented drug product with the publicly available ex-factory prices of the same dosage form and strength of the same medicine sold in the countries listed in the Regulations (France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the U.K. and the U.S.).

The Median of the International Prices (MIP) test is mainly used for category 2 drugs but may also be applied to category 3 drugs when it is impossible or inappropriate to identify comparable drugs in Canada.

The introductory price is considered excessive if it exceeds the median price of the international prices of the same medicine.

The Highest International Price Comparison (highest IPC or HIPC) test: In addition to the aforementioned tests, the Guidelines state that the Canadian price can never be the highest relative to the prices of the same medicine in the comparator countries.

In the introductory price review, this test is relevant when a category 3 drug price passes the TCC test but the price is the highest in the world. In such cases the MNE price is set by the highest international price and not the highest price of the therapeutic comparators.

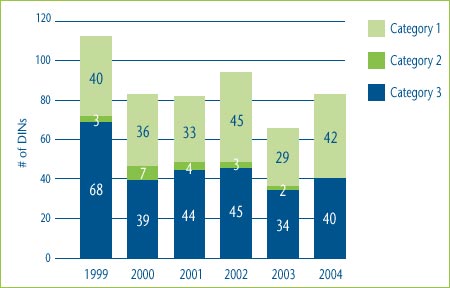

Figure 2 shows the percentage of category 3 DINs whose MNE price would have been determined by the highest IPC test if the patentee had chosen to price to the maximum allowable price based on the TCC test. In 2004 for example, 20% of the MNE prices would have been determined by the highest IPC test if the patentee had chosen to price to the maximum allowable price based on the TCC test.

Figure 2: Comparison of Maximum Allowable TCC Price to Highest Price in Comparator Countries, 1999-2004

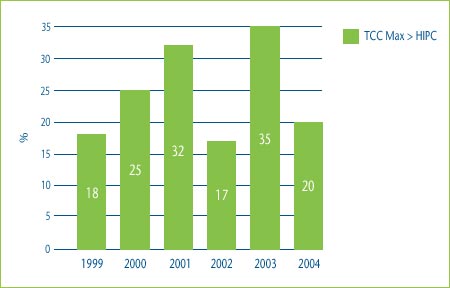

Figure 3 shows the percentage of category 3 DINs whose price would have been higher than the median of the international prices in the countries used for comparison purposes had the patentee chosen to price to the maximum allowable price based on the TCC test. In 2004 for example, 65% of DINs would have been priced higher than the median IPC if the patentee had chosen to price to the maximum allowable price based on the TCC test. This means that in 65% of the cases in 2004, a category 3 DIN could have achieved a “price premium” above what would have been allowed for a category 2 (breakthrough or substantial improvement) drug and it still would have been determined to have been priced within the Board's current Guidelines.

Figure 3: Comparison of Maximum Allowable TCC Price to the Median IPC, 1999-2004

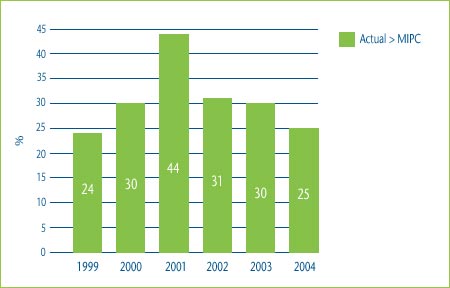

Figure 4 shows the percentage of category 3 DINs that were priced higher than the median of the international prices in the countries used for comparison purposes. It shows the proportion of category 3 DINs that actually achieved a Canadian price premium over the price that would have been allowed had the drug been considered “a breakthrough”. For example, in 2004 25% of the prices of category 3 DINs, whose price was not considered excessive by virtue of a TCC test, exceeded the median international price.

Figure 4: Comparison of the Actual Category 3 Price to Median IPC, 1999-2004

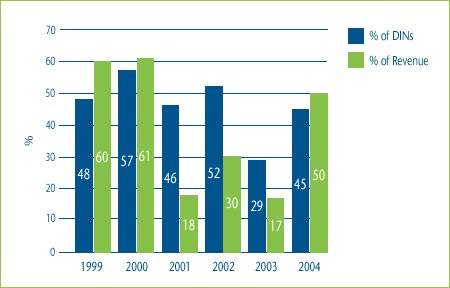

Figure 5 shows the percentage of category 3 DINs that were priced within 10% of the maximum allowable price based on a TCC test for the years 1999 to 2004. It also shows the percentage of the total revenue that was generated by these DINs. As can be seen in this figure, in 2004 45% of DINs, representing 50% of the revenues of all category 3 DINs, were priced within 10% of the maximum allowable price based on the TCC test. Over time, this could result in increases in the average prices of drugs in a particular therapeutic class.

Figure 5: % of DINs priced within 10% of the Maximum Allowable TCC Price and % of Total Revenue for DINs: 1999-2004

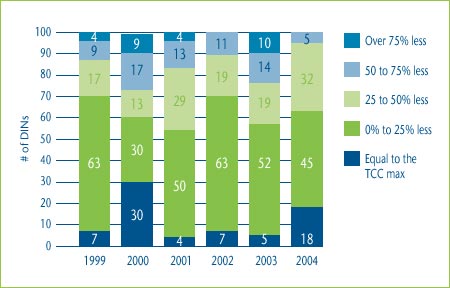

Figure 6 shows the distribution of the prices of category 3 DINs in relation to the maximum allowable prices based on a TCC test. In 2004, 18% of DINs were priced at the maximum price based on the TCC test and an additional 45% were priced within 25% of the maximum.

Figure 6: Distribution of Category 3 New Drug Prices relative to the Maximum Allowable TCC Price, 1999-2004

|

Question 1:

Are the price tests currently used to review the prices of new medicines in the various categories appropriate for that category? Why? Why not? If not, how could these tests be amended to improve their appropriateness?

Question 2:

If you think that medicines that offer "moderate therapeutic improvement" should be distinguished from medicines that provide "little or no therapeutic improvement" what would the appropriate new price test be?

Question 3:

For price review purposes, "comparable medicines" are medicines that are clinically equivalent.4 Do you have any suggestions as to principles or criteria that should be used in determin-ing how to identify "comparable medicines" for the purpose of inclusion in the above price tests?

Question 4:

Under the current Guidelines, Board Staff compares the Canadian average transaction price of the new medicine to the prices of the same medicine sold in the seven countries listed in the Regulations. However, Section 85(1) of the Patent Act states that the Board should take into consideration "the prices of other comparable medicines in other countries". Should the Guidelines address this factor?

If so, how could this factor be incorporated into the price tests for new medicines?

|

3 Dosage forms include, among other groups: oral solid (e.g., capsule, tablet, caplet); oral liquid (e.g., drops, solutions, powders for solution or suspension); topical (e.g., aerosol, cream, patches, powder), etc.

4 The World Health Organization's Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System is used as a starting point in the selection of comparable medicines. Comparable medicines will typically be those in the same fourth level of the ATC sub-class. In some cases, it may be appropriate to select from other levels of the same sub-class or even from other sub-classes. At a minimum, the comparable medicine will have the same primary indication and therapeutic use as the new medicine under review, but selection criteria could also include: mode of action; spectrum of activity; or chemical family. The Guidelines also provide that the Board Staff may omit any product it considers not clinically equivalent or unsuitable for comparison.

Issue 3 Should the Board’s Guidelines address the direction in the Patent Act to consider “any market”?

Context:

In the event that the Board finds that a price is excessive, it can order a price reduction. Section 83 of the Act provides that the Board may make such a finding and order in respect of the price at which a patented medicine is being sold in any market in Canada (emphasis added). Currently, the Board uses the average transaction price (ATP) for Canada as a whole to conduct the various price tests. The ATP means the price received by patentees from within the overall Canadian market, to conduct the various price tests.

Generally, the ATP is calculated as follows:

|

Total net revenues:

total revenues from the sale for all provinces/territories and all classes of customer for all package sizes of the DIN (minus) the value of drugs given as a promotion, or the value of rebates, discounts, refunds, free goods, free services, gifts and other such benefits.

Divided by:

Number of units sold.

|

Given that the current price review process is based on the calculation of a single average transaction price for all of Canada, it is possible for different customer classes (wholesalers, hospitals, pharmacies or others) within or across provinces and territories to pay a higher/lower price than others. As a result, some stakeholders are concerned that if some provinces/ territories and/or classes of customer negotiate price concessions below the maximum non-excessive price (MNE), the offset may be that other provinces/ territories and/or classes of customer will pay higher prices (above the MNE).

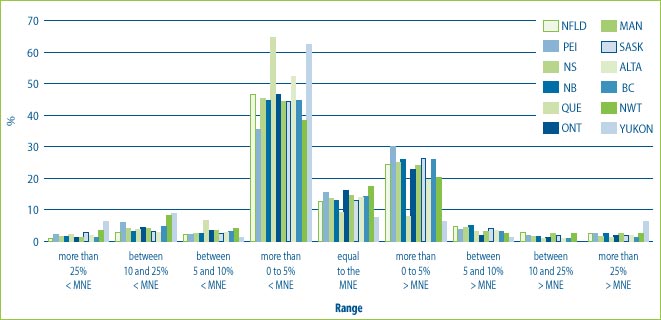

For purposes of considering the issue of any market for new medicines introduced in 2004, Board Staff calculated an ATP for each new DIN introduced in 2004 based on the total net revenues for each province and territory in 2004 and an ATP for each new DIN introduced in 2004 based on the total net revenues for each class of customer (hospitals, pharmacies, wholesalers and others) in 2004. These ATPs were then compared to the MNE price established for 2004 for each new DIN introduced in 2004.

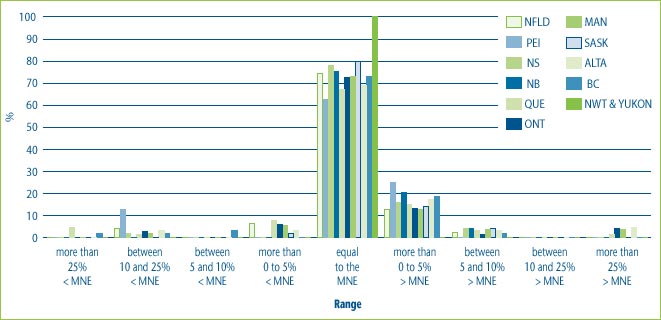

Figure 7, illustrates that in the majority of cases (i.e., between 74% and 89% of cases) the prices charged at the provincial or territorial level are in the range of plus or minus 5% of the MNE price. However, in a small percentage of cases, prices in the provinces and territories are as much as 25% above price. Conversely, in a small percentage of cases, prices in the provinces and territories are as much as 25% below the MNE price.

Figure 7: % of DINs that deviate from the MNE by Province and Territory for new drugs introduced in 2004

Note: This chart includes all new DINs whose introductory prices were reviewed and found to be within the Guidelines including those introductory prices that did not trigger the investigation criteria (introductory price is 5% or more above the MNE, or excess revenues are $25,000 or more). For full details on investigation criteria see p. 41 of the Compendium of Guidelines, Policies and Procedures. Due to the small number of drugs sold to the Northwest Territories and the Yukon, their statistics have been combined.

Numbers have been rounded to one decimal place.

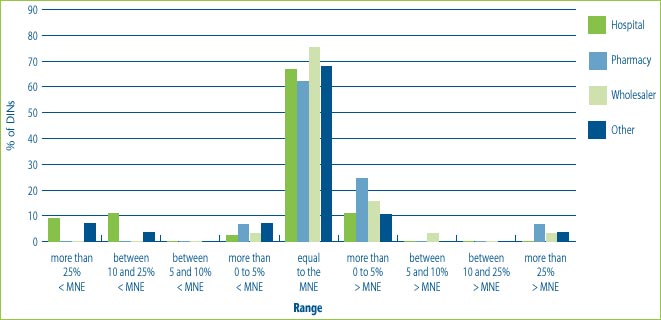

Figure 8 illustrates that the introductory prices of new drug products for most customers, regardless of customer class, are up to 5% above the MNE price and in a smaller percentage of cases up to 5% below the MNE price. This figure also shows that hospitals are more likely than wholesalers or pharmacies to receive price concessions. This could be the result of special bulk purchase contracts made with hospitals, and the nature of hospital negotiation practices. At the same time, some introductory prices for some customer classes have been more than 25% above the MNE price.

Figure 8: % of DINs that deviate from the MNE by Customer Class for drugs introduced in 2004

Note: This chart includes all new DINs whose introductory prices were reviewed and found to be within the Guidelines including those introductory prices that did not trigger the investigation criteria (introductory price is 5% or more above the MNE, or excess revenues are $25,000 or more). For full details on investigation criteria see p. 41 of the Compendium of Guidelines, Policies and Procedures.

Numbers have been rounded to one decimal place.

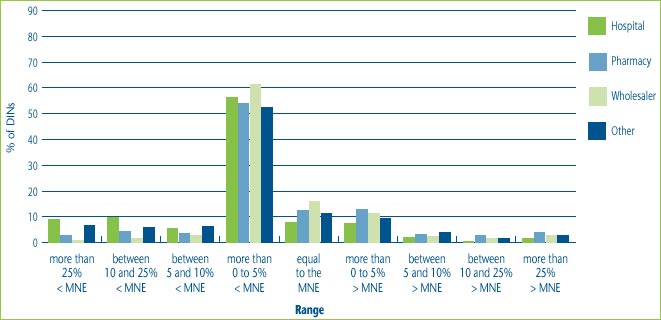

For purposes of considering the issue of any market for all drugs, Board Staff calculated an ATP for each DIN based on the total net revenues for each province and territory and an ATP for each DIN based on the total net revenues for each class of customer (hospitals, pharmacies, wholesalers and others). These ATPs were then compared to the MNE price established for 2004 for each DIN.

Figure 9 illustrates that in many cases the prices charged to provinces and territories are in the range of plus or minus 5% of the MNE price. However, in a small percentage of cases, prices charged to the provinces and territories are as much as 25% above the MNE price. It also shows that hospitals are more likely than wholesalers and pharmacies to receive price concessions. This could be the result of special bulk purchase multi-year contracts made with hospitals. At the same time, some customers, even hospitals have been charged prices that are more than 25% above the MNE price.

Figure 9: % of the DINs that deviate from the MNE by Province and Territory for all drugs sold in 2004

Note: This chart includes all new DINs whose introductory prices were reviewed and found to be within the Guidelines including those introductory prices that did not trigger the investigation criteria (introductory price is 5% or more above the MNE, or excess revenues are $25,000 or more). For full details on investigation criteria see p. 41 of the Compendium of Guidelines, Policies and Procedures.

Numbers have been rounded to one decimal place.

Figure 10 illustrates that for all patented drugs sold in Canada most customers, regardless of customer class, are charged prices that are up to 5% below the MNE price. It also shows that hospitals are more likely than wholesalers and pharmacies to receive price concessions. This could be the result of special bulk purchase multi-year contracts made with hospitals. At the same time, some customers, even hospitals have been charged prices that are more than 25% above the MNE price.

Figure 10: % of DINs that deviate from the MNE by Customer Class, for all drugs sold in 2004

Note: This chart includes all new DINs whose introductory prices were reviewed and found to be within the Guidelines including those introductory prices that did not trigger the investigation criteria (introductory price is 5% or more above the MNE, or excess revenues are $25,000 or more). For full details on investigation criteria see p. 41 of the Compendium of Guidelines, Policies and Procedures.

Numbers have been rounded to one decimal place.

Question 1:

Given the price variations by provinces/ territories and classes of customer illustrated in the previous figures, is it appropriate for the Board to only consider an ATP calculated based on the total revenues from the sales for all provinces/territories and all classes of customer? Why? Why not?

Question 2:

If the current ATP calculation is not appropriate, should the Board review the prices to the different classes of cus-tomers and/or the different provinces and territories for all DINs? Or should this level of review be done on a case-by-case basis, where there is a significant variation in the prices charged?

Annex A - Development of the Guidelines

In the development of its Excessive Price Guidelines, the Board undertook extensive consultations with its various stakeholders. The first draft of the Guidelines was published in the first issue of the PMPRB's Bulletin, in July 1988. The Bulletin has since been replaced by the NEWSletter and Notice and Comment documents as the vehicles to communicate information in a timely manner.

The Excessive Price Guidelines, 1988

The initial Guidelines were issued in July 1988, and modified in 1989.

Criteria for Review of Patented Medicine Prices

For price review purposes, the Board decided to distinguish existing patented drugs (i.e., those sold prior to December 7, 1987 the date the amendments to the Act that created the PMPRB came into effect) from new patented drugs (i.e., those first sold on or after December 7, 1987). After careful consideration of the factors in the Act to be used in determining whether a price is excessive, the Board decided that it was reasonable to place the greatest weight on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) factor in assessing the prices of existing medicines and to establish the benchmark price as the selling price on December 7, 1987. For new patented medicines, the Board considered it reasonable to use the international price of the medicine and the therapeutic class factors to establish the benchmark price.

Role of Costs in the Review Process

When establishing the Excessive Price Guidelines, the Board expected to rely primarily on the review criteria set out in subsection 85(1) to determine whether a price is excessive. Thus, the Guidelines are based on these factors and the costs of making and marketing are not considered by Board Staff. Where Board Staff cannot determine whether a price is excessive by applying the Guidelines, the matter must be referred to the Chairperson to determine if a public hearing is in the public interest.

Other Matters

Markets and Prices: Because patent rights are national in scope and the Board is empowered to make determinations only with respect to the prices of (patented) medicines sold by patentees, the Board considered it appropriate to conduct price reviews based on the price within the overall Canadian market. As a result, the Board stated that its review would normally be based on average prices from sales for the periods January 1 to June 30 and July 1 to December 31. However, in light of the specification in the Act with respect to any market in Canada, the Board has always maintained that prices charged to particular classes of customers (e.g., wholesalers, hospitals, pharmacies, or others) and prices charged in particular provinces or territories may be reviewed where specific evidence indicates it would be appropriate.

In July 1989, the Board issued modifications to supplement and elaborate on the Excessive Price Guidelines published in July 1988.

Drug Categories and Associated Price Tests

Category 1 drug products are a new strength (e.g., 50 mg v. 100 mg) or a new dosage form (e.g., tablet v. capsule) of an existing medicine.

Reasonable Relationship (RR) test considers the association between the price of a new strength of the new medicine and the price of the same medicine in the same or comparable dosage forms. The reasonable relationship test defines a maximum non-excessive introductory price for a category 1 new patented drug product.

Category 2 drug products represent a therapeutic breakthrough or provide substantial improvement over comparable existing medicines.

International Price Comparison (IPC) test compares the average transaction price of the new patented drug product under review with the publicly available ex-factory prices of the same dosage form and strength of the same medicine sold in the countries listed in the Regulations (France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the U.K. and the U.S.). A breakthrough/substantial improvement drug cannot be priced higher than the median of the prices in these comparator countries.

Category 3 drug products provide moderate, little or no therapeutic advantage over comparable medicines. Therapeutic Class Comparison (TCC) test compares the price of the new patented drug product under review to the prices of other clinically equivalent drug products that are used to treat the same disease and that are sold in the same markets in Canada, at a price that the Board considers not to be excessive.

Response of Stakeholders

At that time, the consultations generated submissions from various stakeholder groups. Among other things, the Board received comments on the international price comparison, the therapeutic class comparison and a reward for modest improvement.

International Price Comparison: While some members of the patented pharmaceutical industry did not favour the use of the international price comparison on the grounds that it had limited usefulness, the industry as a whole objected strongly to the use of the median of the prices in the seven comparator countries. The industry considered the median an arbitrary and inflexible measure having inherent statistical problems of measurement. On the other hand, other parties supported the use of the median as the standard. In their opinion, Canada should not be expected to contribute at a premium level in relation to its comparator countries.

The Board disagreed that the international price comparison was inappropriate because the Act clearly directs the Board to consider the prices at which a medicine is sold in other countries in determining if a price is excessive. The Board retained the international price comparison and continued to use the median price of the seven countries as its guideline for the international price comparison.

Therapeutic Class Comparison: Many members of the pharmaceutical industry suggested that the Board should exclude non-patented medicines and generic copies from the therapeutic class comparison. Some members of the patented pharmaceutical industry objected to using the therapeutic class comparison to determine if a price was excessive, particularly where prices within an entire class were low because of generic drugs or because all of the comparators in the class were older medicines. Conversely, other interested parties expressed concern that the therapeutic class comparison may allow all new medicines to be priced at the top of the therapeutic class, which could inappropriately raise the average Canadian price.

The Board noted the Act directs it to consider the prices of other medicines in the therapeutic class and the Act does not differentiate patented medicines from non-patented or generic medicines in this regard. The Board also noted the concerns of other parties that the therapeutic class comparison might put upward pressure on Canadian prices of patented medicines. At that time the Board believed this would not be a serious problem because market forces would penalize any new medicine priced as high as the highest in its class where it does not at least offer comparable benefits. However, the Board committed to monitor the pricing behaviour of new medicines over time to determine whether its Guidelines were appropriate. The Board retained the therapeutic class comparison.

Modest Improvement: The patented pharmaceutical industry expressed serious concern that the guidelines did not provide a suitable financial reward for new medicines that provide modest or moderate improvements over existing medicines. By comparison, other interested parties expressed the view that the Board should ensure that only new medicines which are truly innovative are rewarded.

The Board´s Guidelines signalled its wish to distinguish those medicines that provide breakthrough or substantial improvement over existing therapies from other medicines. While it had considered the concept of adjusting the maximum non-excessive price based on some determination of the therapeutic value of the medicine (e.g., in terms of safety, efficacy, dosage regimen, etc.) this was seen as unworkable.

Revisions to the Guidelines, 1993

In August 1992, the Board announced that it was examining certain issues related to the Guidelines. The proposed modifications were published in Bulletin 9 and interested parties were invited to provide written submissions. Among other things, the Board proposed that the introductory price of a category 3 drug would be considered excessive if it exceeded either the TCC or the median of the international prices (MIP). The proposal was intended to address evidence that many new drugs in category 3 were introduced in Canada in 1990 and 1991 at prices higher than the median international price for the same drug.

At that time the Board was also concerned about the prices of existing medicines in relation to international prices. Throughout these consultations the Board affirmed the principle that the prices of patented medicines should not, in general, exceed prices in other countries.

After extensive consultations in 1993, the Board decided to revise the CPI-adjustment methodology and add the Highest IPC rule to the Guidelines. The Highest IPC rule states: the price of patented drug product will be assumed to be excessive if it exceeds the prices of the same drug products in all countries listed in the Regulations. It did not, however, decide to constrain the price of a category 3 drug by changing the MNE test to be the lower of the TCC and the MIP.

The Road Map for the Next Decade, 1999

In 1997, the Board undertook a year long public consultation on its role, function and methods. The Board reported on these consultations through the release of the Road Map for the Next Decade, and attached papers.

Throughout the consultations, stakeholders expressed concerns about the Guidelines, although they were divided as to whether they were too generous or too restrictive. There were many submissions about category 3 drugs that is, new medicines that do not represent a breakthrough or substantial improvement over existing drugs.

The Working Group on Price Review Issues, 1999-2002

The Board emerged from a period of unprecedented consultations with a commitment to continue consultations with its stakeholders. In this context, the Board established the Working Group on Price Review Issues (Working Group), early in 1999, to review, analyze and provide reports to the Board for consideration on certain issues including the Excessive Price Guidelines for drugs in category 3.

The Working Group's recommendations on the category 3 Guidelines reaffirmed the appropriateness of many of the Board's existing practices, or suggested where some minor improvements could be made. The Working Group did not recommend any changes to the price limits established by the Guidelines but it did recommend that the Guidelines should better reflect the relative value of new patented drugs. However, the Working Group did not define value or its implications for the Guidelines.

Conclusion

As is evident from the above, the Board has taken steps to consult on and, as needed, amend its Guidelines to ensure that they remain both relevant and appropriate to the current pharmaceutical environment. This is also the goal of the current consultation process. At the same time, the Board recognizes that its Guidelines can not foresee every possible circumstance that might arise in determining whether a patented medicine is being or has been sold at an excessive price. Nevertheless, the Board believes that the Guidelines should provide transparency and predictability in the price review process, and a useful standard for a prima facie assessment of whether or not, based on the factors stated in the Patent Act, the price of a patented medicine is excessive.

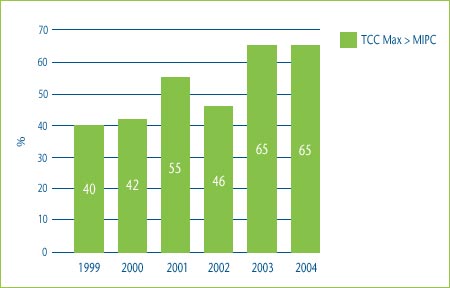

Annex B - The Patented Price Review Process

In Canada, new patented medicines are assessed by Health Canada to ensure that they conform with the Food and Drugs Act and the Food and Drug Regulations with respect to safety, quantity and efficacy. For a new medicine to be marketed or distributed in Canada it must be granted a Notice of Compliance (NOC). A medicine may also be sold with specified restrictions before receiving a NOC, either as an Investigational New Drug or under Health Canada's Special Access Program (SAP). SAP drugs have not been approved for sale in Canada but a physician may request authority to obtain the drug from outside Canada for a specific patient.

For the jurisdiction of the PMPRB to crystallize, a medicine must be both patented and sold. However it is the policy of the Board to retroactively review the price at which the medicine was sold during the patent pending period.

While patentees are to inform the PMPRB of an “intention to sell” a new patented medicine, the PMPRB´s price review process is ordinarily triggered by the patentee filing information on the identity of the medicine once the medicine is actually patented and being sold in Canada. At specific times and for specific periods as laid out in the Patented Medicines Regulations (Regulations), the patentee is also required to report price and sales data. In addition to the aforementioned, patentees normally make a submission regarding how the medicine should be categorized (line extension, breakthrough or moderate, little or no improvement), along with proposed comparators, dosage regimens and supporting clinical studies. However, a Scientific Review can be started with just a Product Monograph.

The scientific review involves an evidencebased process that determines the appropriate category for the drug and appropriate therapeutic comparators and comparable dosage regimens. It does not consider any pricing information relating to the new product. All new active substances are referred to the Human Drug Advisory Panel (HDAP) to review and evaluate clinical trial and other scientific evidence.

Based on the categorization of the drug, Board Staff conducts the appropriate price tests as prescribed by the Guidelines. If the patentee's selling price is not above the maximum non-excessive price (MNE) established by the appropriate price tests, the patentee's price is deemed to be “within the Guidelines”. This selling price then sets the benchmark for future monitoring of prices. Price increases for existing drugs are limited to the PMPRB's Consumer Price Index (CPI)-adjustment methodology.

If the price at which the medicine is sold is considered excessive and triggers the investigation criteria set out in the Guidelines, Board Staff commences an investigation. There are three ways to resolve an investigation:

- further submissions by the patentee and information obtained by Board Staff result in a determination that the price is within the Guidelines;

- the patentee voluntarily agrees to reduce the price and pay back any excess revenues; or

- the matter is referred to the Board Chairperson who decides whether it is in the public interest to hold a public hearing.

Illustration of the Price Review Process for Patented Medicines