ISBN: 978-0-660-03054-8

Catalogue number: H82-19/2015E-PDF

PDF version (2.39 MB)

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is a consumer protection agency with a dual regulatory and reporting mandate. It ensures that the prices of patented medicines sold in Canada are not excessive and provides stakeholders with pharmaceutical trends information to help them make informed choices.

1. Message from the Chairperson

Canada, like many countries, is facing escalating health care costs, as payers everywhere are struggling to reconcile finite drug budgets with patient access to promising but costly new health technologies. Despite recent stabilizing trends in spending on prescribed drugs, growth in Canadian patented drug sales continues to outpace growth in the seven countries to which we compare ourselves in the Patented Medicines Regulations Footnote 1, with the exception of the United States. Canadian patented drug prices are now the third highest of these comparator countries, nearly at par with Germany.

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) was conceived in 1987, through amendments to the Patent Act, as part of a major overhaul of Canada’s drug patent regime, which sought to balance potentially competing policy objectives. On the one hand, the government strengthened patent protection for drugs in an effort to encourage more pharmaceutical industry research and development (R&D) investment in Canada. On the other, it sought to mitigate the financial impact of that change on Canadians by creating the PMPRB, a consumer protection agency with a mandate to ensure patented drug prices in Canada are not “excessive”.

The legislation which gave rise to these changes, Bill C-22, was very contentious at the time, and the credibility and effectiveness of the PMPRB as a regulator was seen as key to ensuring the long term viability of the policy compromise embodied within it.

In the ensuing years, intellectual property protection for pharmaceuticals in Canada has been further strengthened through a succession of legislative and regulatory reformsFootnote 2 while the PMPRB’s legal framework has remained essentially unchanged. Over the same period, many other developed countries with public health care systems have introduced measures to address affordability issues, maximize value for money and keep pace with a rapidly evolving pharmaceutical market.

With these international developments as backdrop, the recent coupling of relatively high patented drug prices and record low pharmaceutical R&D in Canada has given rise to legitimate questions regarding the extent to which the PMPRB is meeting the original policy objectives which impelled its creation over 25 years ago. Accordingly, In 2014, the PMPRB initiated a year-long strategic planning process in an effort to chart a fresh course for the next quarter century that would see the organization reaffirm itself as an effective safeguard against excessively priced patented medicines and an even more valued source of market intelligence for policy makers and payers.

As explained below, the strategic objectives that have been identified for the coming years are based on a thorough assessment by the PMPRB of how to respond to the current and pending threats and opportunities in its operating environment. That response is inspired by a vision as to how the PMPRB can best leverage its strengths and unique legislative remit to complement the efforts of its federal, provincial and territorial partners and other stakeholders in advancing our common goal of a sustainable health system. The broad strokes of how that vision will inform the daily work of the PMPRB going forward is expressed in its reinvigorated mission statement, a more aspirational and uplifting version of the original, as befits the challenges that lie ahead.

2. Executive Summary

Background

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) was created in 1987, through amendments to the Patent Act, as part of a major overhaul of Canada’s drug patent regime, which gave pharmaceutical patentees longer periods of market exclusivity for their products. The originally stated purpose of the PMPRB was to ensure pharmaceutical companies did not abuse their newly strengthened patent rights by charging consumers “excessive” prices for patented medicines during the statutory monopoly period. Consumer protection was one of the five pillarsFootnote 3 or founding principles underlying these legislative amendments.

Prior to the establishment of the PMPRB, Canadian patented drug prices were outpacing the general rate of inflation and were well above the median of foreign prices, second only to the United States among the PMPRB7 Footnote 4. Since that time, prices have generally remained below both inflation and the international median. More recently, however, Canadian patented drug prices have been steadily rising relative to prices in the PMPRB7 and now stand third highest, nearly at par with Germany.

As drug prices in Canada rise, R&D spending by pharmaceutical patentees is declining, having fallen to 5.4% of sales in 2013, the lowest recorded figure since the PMPRB began reporting on R&D in 1988.

The coupling of high patented drug prices and record low investment in R&D by pharmaceutical manufacturers calls into question the effectiveness of the current regime in meeting its original policy objectives.

Objective

The objective of this Strategic Plan is for the PMPRB to embrace the threats and opportunities in its operating environment in a way that enables it to emerge stronger and more effective than before.

Methodology and findings

The PMPRB’s year-long strategic planning process has culminated in a new vision and a revised mission statement. For 2015-18, the PMPRB has the following strategic objectives:

Strategic objective 1: Consumer-focused regulation and reporting

Strategic objective 2: Framework modernization

Strategic objective 3: Strategic partnerships and public awareness

Strategic objective 4: Employee engagement

Purpose

This strategic plan is intended to be a high-level document that will guide the implementation of the PMPRB’s strategic objectives through detailed operational and human resources plans to be developed by Staff on a yearly basis.

3. The Role of the PMPRB

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is an independent quasi-judicial body established by Parliament in 1987 under the Patent Act (Act). Although the PMPRB is part of the Health Portfolio, because of its quasi-judicial responsibilities it carries out its mandate at arm’s-length from the Minister of Health, who is responsible for the sections of the Act pertaining to the PMPRB.

It also operates independently of Health Canada, which approves drugs for safety and efficacy; other Health Portfolio members, such as the Public Health Agency of Canada, and the Canadian Institute for Health Research; and provincial drug plans, which approve the listing of drugs on their respective formularies for reimbursement purposes.

The PMPRB is a consumer protection agency with a dual regulatory and reporting mandate. Its regulatory mandate is to ensure that the prices of patented medicines sold in Canada are not excessive. Its reporting mandate is to provide stakeholders with pharmaceutical trends information to help them make informed choices.

The PMPRB is divided into Board “Staff” and Board “Members.” Staff is comprised of public servants who are responsible for carrying out the organization’s day to day work. Members are Governor-in-Council appointees who preside over hearings into allegations of excessive pricing. The Chairperson of the Board is designated under the Act as the Chief Executive Officer of the PMPRB, with the authority and responsibility to supervise and direct its work.

a. Regulatory mandate

The PMPRB regulates “factory gate” ceiling prices and does not have jurisdiction over wholesale prices or retail prices charged by pharmacies. Staff reviews the prices that patentees charge for all patented drug products sold in Canada. If Staff determines that the price of a patented medicine appears to be excessive, and cannot reach a consensual resolution of the issue with the patentee, the Chairperson may hold a hearing on the matter if she is of the view that it is in the public interest. The PMPRB’s adjudicative functions are carried out by Board Members. At a hearing, a panel composed of Board members acts as a neutral arbiter between Board Staff and the patentee. The Chairperson decides the composition of members on a panel but, as a matter of policy, does not usually herself participate as a panelist. Provincial and territorial ministers of health may also appear before the panel as statutory parties, and other interested persons or groups may be granted leave to participate as interveners. In the event that a panel finds that the price of a patented medicine is in fact excessive, it can order a reduction of the price to a non-excessive level. It can also order a patentee to offset any excess revenues and, in cases where the panel determines there has been a policy of excessive pricing, it can double the amount to be offset.

b. Reporting mandate

The PMPRB reports annually to Parliament through the Minister of Health on its price review activities, the prices of patented medicines and price trends of all prescription drugs, and on the research and development (R&D) expenditures reported by pharmaceutical patentees, as required by the Act. In addition, as a result of the establishment of the National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System (NPDUIS) by federal, provincial and territorial (F/P/T) ministers of health in 2001, the PMPRB conducts critical analysis of price, utilization, and cost trends for patented and non-patented prescription drugs. This function is aimed at providing F/P/T governments and other interested stakeholders with a centralized credible source of information on pharmaceutical trends.

4. The Pharmaceutical Environment in Canada

a. Introduction

It is often noted that Canada is the only developed country with a publicly funded health care system that does not include universal drug coverage. Of the approximately $29 billion spent on prescription drugs in 2013, private payers accounted for 58% of payments (insurers 35% and out-of-pocket 23%) and public payers (mainly the provinces and territories) for the remaining 42%.

As such, Canada is also fairly unique in that it does not have a national purchasing authority that can harness the buying power of the state to negotiate lower prices on behalf of the entire population. In its stead is a complex web of multiple, overlapping federal, provincial, territorial and private sector organizations, arrangements and initiatives directed at containing, if not controlling, drug costs. The PMPRB is the primary federal lever in that regard; its jurisdiction originating in the federal constitutional power over patents of invention and discovery. It currently reviews and sets price ceilings for all patented medicines sold in Canada, based on the level of therapeutic improvement, domestic prices, prices in the seven countries identified in the Patented Medicines Regulations (the PMPRB7), Footnote 5 and changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

The PMPRB was created as part of extensive amendments to the Act which gave pharmaceutical patentees longer periods of market exclusivity. The stated purpose of the PMPRB was to ensure that consumers are protected from excessive prices for patented drugs during the newly strengthened monopoly period.

In 1987, when the current drug patent regime was conceived, the government of the day was determined to increase the level of investment in pharmaceutical R&D in Canada. Policy makers believed that patent protection and price were key drivers of such investment. The choice was thus made to offer a comparable level of patent protection and pricing for drugs as existed in countries with a strong pharmaceutical industry presence, on the assumption that Canada would come to enjoy comparable levels of R&D. In return for amendments to the Act which strengthened drug patent protection, Canada’s Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies (Rx&D)Footnote 6 committed to double R&D output from 1987 levels of less than 5% of sales to 8% by 1991 and 10% by 1996.Footnote 7

Impact of policy on drug prices and R&D

Prior to the establishment of the PMPRB, Canadian patented drug prices were outpacing the general rate of inflation as measured by CPI and were 23% above the median of foreign prices, second only to the United States (US) among the PMPRB7. Since that time, annual price increases have remained well below CPI almost without exception, whereas prices overall have been at or below the international median following important revisions to the PMPRB’s guidelines in 1994.Footnote 8 In terms of R&D, patentees made significant progress in the early to mid-1990s, with Rx&D members reaching their target of 10% of sales three years ahead of schedule in 1993, before eventually peaking at 12.9% in 1997.

More recently, however, Canadian patented drug prices have been steadily rising relative to prices in the PMPRB7. Whereas in 2005 Canadian prices were third lowest of these seven countries, in 2013 they were third highest, nearly at par with Germany but still well below the US. Among the five lower priced countries of the PMPRB7 in 2013, prices in the UK, France and Italy were all 20% below Canadian prices. Outside of the PMPRB7, prices in Australia, Austria, Spain, Finland, the Netherlands and New Zealand were 17% to 37% lower than Canadian prices in 2013. Looking beyond just patented drugs to all prescription drugs, Canada spends more per capita and as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) than most other OECD countries, with the exception of the USFootnote 9.

As prices in Canada rise, R&D is declining. Since 2003, Rx&D members have failed to meet their 10% commitment and the latest publicly reported ratio stands at a 5.4% of sales. This is the lowest recorded figure since 1988, when the PMPRB first began reporting on R&D. In contrast, the average R&D ratio of the PMPRB7 countries has held steady at above 20%.Footnote 10

Recent provincial and territorial joint pricing and purchasing initiatives

As part of the 2004 National Health Accord, the federal, provincial and territorial governments committed to a 10 year plan to strengthen health care. A key part of that plan was the establishment of a National Pharmaceuticals Strategy (NPS), which directed Health Ministers to examine and report back on nine elements seen as integral to ensuring equitable access to pharmaceuticals for all Canadians. A more streamlined agenda reduced that list to five priority areas by 2006, which included the establishment of a national common drug formulary and bulk pricing and purchasing strategies.

Although federal-provincial-territorial collaboration on the NPS subsequently waned, provinces and territories continued to jointly explore bulk pricing and purchasing strategies. In 2010, this work led the Council of the Federation to establish the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA). The pCPA conducts joint provincial/territorial negotiations for brand and generic drugs to achieve greater value for publicly funded drug programs. As of May 31, 2015, the pCPA has completed 71 joint negotiations on brand drugs. When combined with the price reductions in generic drugs achieved under the Value Price Initiative, another Council of Federation joint pricing strategy, annual savings are said to be in excess of $315 million. However, the disaggregated savings attributable to brand drugs alone is not known, as the discounts off public list prices negotiated under the pCPA are kept confidential at the insistence of pharmaceutical manufacturers.

These confidential deals, called product listing agreements (PLA), enable manufacturers to price discriminate between payers and have become increasingly common in recent years. While the rebates negotiated through PLAs are a way for public payers to contain costs, private insurers claim that they are driving up prices in the private market, as individual insurance companies wield less bargaining power than most public payers and have no private sector equivalent to the pCPA.Footnote 11

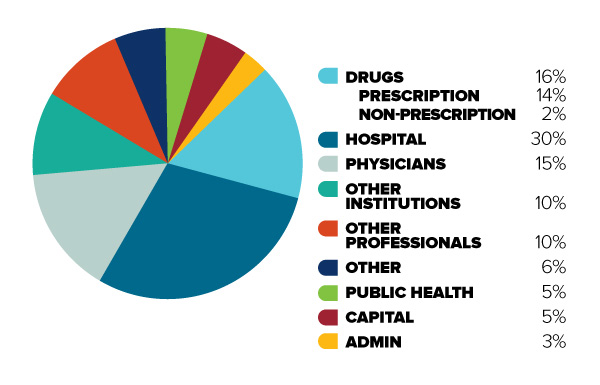

Figure 1: Total Canadian

Figure description

This diagram illustrates the break-down of total Canadian health care spending in 2013 into different categories. It is intended to demonstrate the relative significance of different objects of health care spending.

In order of decreasing size, the share of total Canadian health care spending is as follows: Hospitals (30%), Drugs (16%, 14% for prescription drugs and 2% for non-prescription drugs), Physicians (15%), Other Institutions (10%), Other Professionals (10%), Public Health (5%), Capital (5%), Administration (3%), and Other (6%).

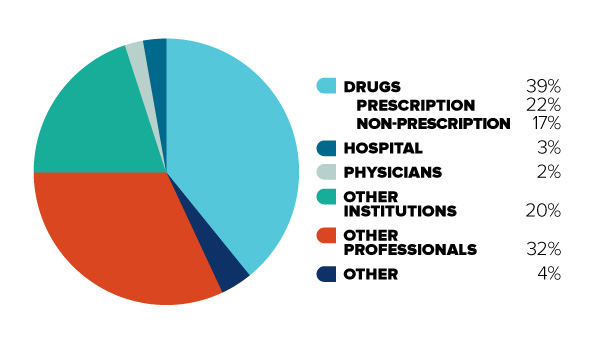

Figure 2: Out-of-pocket (uninsured)

Figure description

This diagram illustrates the break-down of total Canadian health care spending in 2012 for uninsured (or “out-of-pocket”) costs only. It is intended to contrast with Figure 1, to demonstrate that for Canadians with limited insurance coverage, different cost categories are more significant.

In order of decreasing size, the share of total Canadian out-of-pocket health care spending is as follows: Drugs (39%, 22% for prescription drugs and 17% for non-prescription drugs), Other Professionals (32%), Other Institutions (20%), Hospitals (3%), Physicians (2%), and Other (4%).

Recent trends in drug expenditures

As mentioned, Canadians spent approximately $29 billion on prescription drugs in 2013, a significant component of overall health care costs. After sustained double-digit rates of growth in prescription drug expenditures a decade ago, the annual net increase has gradually slowed, reaching 1.2% in 2012Footnote 12, making drugs the slowest-growing of the three major categories of health expenditure.Footnote 13

Changes in the growth of prescription drug expenditures are driven by a number of opposing “push” and “pull” effects. For example, an increase in the beneficiary population and the use of more expensive drugs put upward pressure on expenditures, resulting in a push effect; while generic substitution and price reductions exert a downward pull effect. In any given year and market segment, the weight of these effects may vary, and as a result, the rates of change in prescription drug expenditures evolve over time and vary across public and private drug plans.

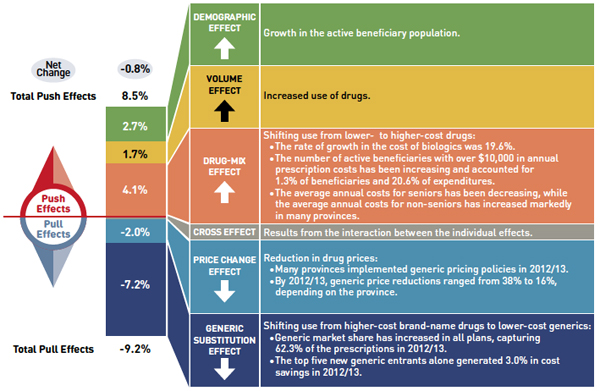

Figure 3: Drug Cost Drivers 2012/13

Figure description

This diagram illustrates drug cost drivers for 2012/13, breaking them out into push (increasing) and pull (decreasing) effects. It shows the totals for the select public drug plans in Canada.

The overall net change in drug costs from 2011/12 to 2012/13 was -0.8%.

The total push effect was 8.5% and included the following key effects:

- The drug-mix effect (4.1%) due to shifting use from lower- to higher-cost drugs:

- The rate of growth in the cost of biologics was 19.6%.

- The number of active beneficiaries with over $10,000 in annual prescription costs has been increasing and accounted for 1.3% of beneficiaries and 20.6% of expenditures.

- The average annual costs for seniors have been decreasing, while the average annual costs for non-seniors have increased markedly in many provinces.

- The volume effect (1.7%) due to the increased use of drugs.

- The demographic effect (2.7%) due to the growth in the active beneficiary population.

The total pull effect was -9.2% and included the following key effects:

- The generic substitution effect (-7.2%) due to shifting use from higher-cost brand-name drugs to lower-cost generics:

- Generic market share has increased in all plans, capturing 62.3% of the prescriptions in 2012/13.

- The top five new generic entrants alone generated 3.0% in cost savings in 2012/13.

- The price change effect (-2.0%) due to a reduction in drug prices:

- Many provinces implemented generic pricing policies in 2012/13.

- By 2012/13, generic price reductions ranged from 38% to 16%, depending on the province.

A cross effect resulted from the interaction between the individual effects. No value is given for the cross effect.

Recent PMPRB-authored NPDUIS studies indicate that the relatively slow growth rates seen in public plans of late can be attributed in large part to the well-known “patent cliff” phenomenon of multiple “blockbuster” drugs coming off-patent within a very short period of time, as well as significant generic price reductions achieved under the Value Price Initiative. These pull effects are largely one-time events, the impact of which is expected to diminish in the coming years as the patent cliff phenomenon runs its courseFootnote 14. In contrast, the cost drivers behind the push effects are long-term trends that are expected to increase significantly, as the population ages and new, higher cost drugs displace the previous generation of therapies.

The most recent reporting from IMS Brogan suggests that Canada may have already turned this cornerFootnote 15. In 2014, total Canadian drug sales increased by 4.4%, and brand drug sales by 5.6%. While every brand market segment grew in 2014, growth in some critical, high priced segments was striking, with expenditures on biologics increasing by 10.4%, and oncology drugs by 12.3%. Even more striking is the fact that 2014 was an unprecedented year for new product launches, with sales totalling $289 million, nearly ten times the historic average. This sudden spike in spending was driven in significant part by the introduction of very high priced drugs to treat Hepatitis CFootnote 16.

Implications for the PMPRB

The coupling of relatively high patented drug prices and record low R&D calls into question the effectiveness of the current regime in meeting its original policy objectives. Since 1987, the empirical evidence has not supported the notion that price and intellectual property protection are important drivers of pharmaceutical R&D investment. There is growing recognition that other factors, such as head office location, clinical trials infrastructure and scientific clusters, are more important determinants of where such investment takes place in a global economyFootnote 17.

This realization, considered against the backdrop of recent provincial and territorial cost containment measures which have resulted in lower drug prices for public payers, gives rise to legitimate questions about the continuing rationale for a federal pharmaceutical regulator in Canada. These questions were very much on the minds of both the Board and Staff as the PMPRB embarked on its year-long strategic planning process. Having recently celebrated its 25th anniversary, the PMPRB finds itself at an important crossroads in its history. The path taken from here will determine whether it remains a relevant and effective federal safeguard in ensuring the sustainability of Canada’s health system, or is reduced to play an ever more marginalized role in that system. The strategic objectives identified in this document are the product of extensive reflection, self-examination and a comprehensive review of the PMPRB’s external and internal operating environment. The careful execution of these priorities in the coming years will enable the PMPRB to build on its prior successes and emerge from this period stronger and more effective than at any time in its almost three decade-long history.

b. Environmental Scan

The PMPRB operates in a complex environment, marked by intersecting and sometimes conflicting political, economic, social, legal, commercial and technological issues and interests.

By its nature, the pharmaceutical industry is one of the most heavily regulated in the world. Canada is no exception, as pharmaceutical regulation is a shared jurisdictional responsibility. At the federal level, Health Canada reviews new drugs for safety, efficacy and quality and the PMPRB sets their ceiling price for as long as they are patented. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies (CADTH), an independent, not-for-profit agency funded by federal, provincial and territorial governments, conducts economic evaluations of new drugs and makes reimbursement recommendations to participating public payers. At the provincial and territorial level, health ministries and drug plan managers decide which drugs to reimburse for their beneficiary populations and negotiate prices directly with pharmaceutical manufacturers. Outside of government, private health insurers manage employer-sponsored drug plans and also negotiate prices directly with manufacturers. The rules governing whether and to what extent private insurers are bound by reimbursement decisions by public drug plans, or benefit from their price negotiations, vary by province.

Despite best intentions, the inevitable result of the above described system is a somewhat fragmented approach to pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement in which key decisions on price regulation, cost effectiveness, market access and price negotiation are often made in silos. This can be contrasted with the more integrated approach that prevails in many other developed countries with a publicly managed health care system where such decisions are made by a single national authority, or closely related authorities working in concert. In countries with multi-payer systems, public and private payers benefit equally from the lower prices that result from this approach.

Although the following scan sets out to capture the most significant factors shaping the PMPRB’s external and internal operating environment, it is by no means exhaustive, nor are the factors listed in any particular order of importance.

External factors

1. International reform to pricing and reimbursement regimes

In 1987, when the PMPRB price referencing model was conceived, the concept of benchmarking domestic prices against prices in other countries was in its relative infancy. Today, price referencing is widely used in international price regulation but increasingly as an adjunct to other forms of cost containment. Between 2010 and 2012 alone, 23 European countries began planning or executed significant reforms to their pharmaceutical price regulatory framework to achieve greater cost savings. More recently, exploratory discussions have been taking place between European health ministries on the possibility of “lifting the veil” on confidential discounts in member countries in order to obtain a single best price for all of Europe.Footnote 18 Two of Europe’s leading patient groups have expressed strong support for this movement, recently calling on national authorities to move towards joint Europe-wide price negotiationFootnote 19.

At the same time as these reforms have been unfolding in Europe, patented drug prices in Canada have been rising relative to the European countries in the PMPRB7. This is particularly evident in the case of Germany, which underwent major reform in 2011. Under Germany’s new Act on the Reform of the Market for Medical Products (Arzneimittelmarkt-Neuordnungsgesetz – AMNOG) law, which is expected to generate €2.2 billion in annual savings, manufacturers must demonstrate that a new drug is superior to the accepted standard of care in that country in order for the drug to enjoy a price premium over existing therapies. If a drug is deemed to have additional benefit, price negotiations ensue; otherwise it is reimbursed at the lowest price among comparators in the same therapeutic class, including much cheaper generic drugs. This approach contrasts with the PMPRB’s current regime, which allows new patented drugs that show slight or no improvement over existing therapies (so-called “me-too” drugs) to be priced at the top of the therapeutic class. This may in part explain why Canadian prices are significantly higher than median PMPRB7 prices for this category of drugs, which account for about 80% of new medicines reviewed by the PMPRB.Footnote 20

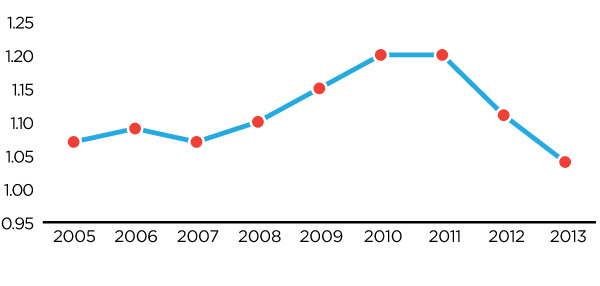

Figure 4: Germany-Canada Price Ratio 2005-2013

Figure description

This diagram illustrates the ratio of German patented medicine prices to Canadian patented medicine prices, over the 2005 to 2013 period. It is intended to illustrate, on average, how much more a German consumer would pay for a given patented drug product than a Canadian consumer in any given year, as well as to show relevant trends.

Over the entire 2005 to 2013 period, German consumers have paid higher prices than Canadian consumers. Over the 2005 to 2007 period this price gap is stable, with German consumers paying approximately 7% more than Canadian consumers. However, beginning in 2008 this price ratio steadily increases, peaking in 2010 with German consumers paying approximately 20% more for the same patented drug product than Canadian consumers. However, since that time, major regulatory reforms in Germany have caused this ratio to rapidly fall, such that by 2013 German prices were only 4% higher than Canadian prices, on average.

2. High cost drugs

In the last few years, many pharmaceutical manufacturers have directed their R&D efforts towards more severe diseases afflicting smaller patient populations. The successful drugs that emerge from this type of R&D do not enjoy the same sales volume as the generation of blockbuster drugs which preceded them but can be much higher priced. At the extreme end of this trend are so-called “orphan drugs,” developed to treat rare and ultra-rare diseases. On occasion, drugs initially conceived for a small patient population can come to enjoy both high volume and high prices. This can occur, for example, when a new, very effective drug for a specific indication enters the market at a high price that is accepted by pricing and reimbursement authorities, but sees its market expand considerably over time as additional indications are approved or as off-label prescribing takes hold. These drugs are sometimes referred to in the industry as “niche busters.”

Many of these high cost drugs are often lumped together in a category referred to as “specialty drugs”, which can comprise biologics, orphan drugs and injectables for certain diseases such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and MS, among others. Although most orphan drugs tend to be specialty drugs, the converse is not true. Global spending on pharmaceuticals is forecast to increase 30% by 2018, driven largely by growth in specialty and oncology drugs. Exceptional growth in these two market segments is expected to account for 40% of that increase over that periodFootnote 21. Global spending on specialty drugs alone is projected to quadruple by 2020.Footnote 22

Many countries are already struggling with the public reimbursement of high-cost drugs. Public and private payers can face enormous pressure to reimburse certain high-cost drugs, even though they may not be considered cost effective by established standards, because of the severity of the illness and a paucity of alternative treatments. In Canada, various strategies have been pursued to address this cost pressure. At the provincial level, since 2006, individual jurisdictions have made efforts to establish catastrophic-drug-coverage programs, albeit with significant disparities between provinces in terms of what drugs are covered, when and for whom. As for the private market, in 2013, members of the Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association (CLHIA) agreed to industry-wide drug pooling to spread the risk of recurrent, high-cost prescription drug claims in order to help mitigate the impact of these costs on employer drug plans.

According to CIHI, between 2007 and 2012, two of the top three drug classes that contributed most to the growth of public drug spending in Canada were anti-TNF drugs and anti-neovascularization agents, both high-priced biologics. Anti-TNF drugs alone accounted for 55% of growth in public spending on prescription drugs during that same period.Footnote 23 In 2014, spending on biologics and oncology drugs grew by double digits and spending on all new drugs increased tenfold.

Health Canada is in the final stages of rolling out a life-cycle-based framework for orphan drugs to facilitate their regulatory approval and attract more such drugs to the Canadian market. This may place added financial pressure on payers and intensify the need for cost containment strategies to ensure maximum patient access to these drugs.

3. Provincial bulk pricing and purchasing

Provincial and territorial drug plans have increasingly taken it upon themselves to find solutions to escalating drug costs by jointly negotiating larger price discounts than could be achieved individually. Since 2010, two such initiatives have emerged from the Council of the Federation’s Health Care Innovation Working Group (HCIWG):

- The pCPA, led by Ontario and Nova Scotia, applies to all brand-name drugs coming forward for funding through CADTH’s Common Drug Review (CDR) or pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR);

- The Health Value Initiative, led by Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, has capped the prices of 14 leading generic molecules at 18% of the equivalent brand price.Footnote 24

The Council of the Federation recently announced that both initiatives are now referred to as the pCPA but that their respective provincial leads remain the same. Further to recommendations contained in an IBM report commissioned by the Council of the Federation, efforts to formalize and embed the initiative are being undertaken over the course of 2015, including the establishing of an office in Ontario, and developing norms for its mission, mandate, guiding principles and governance.

Under the pCPA’s intake process for brand drugs, one province assumes the lead in negotiations with the drug’s manufacturer. If an agreement is reached, the lead province will sign a Letter of Intent with the manufacturer, which is shared with the other pCPA members. Each province and territory reserves its right to make a final decision on whether to fund the drug and enter into a PLA based on the terms in the Letter of Intent.

By joining forces with larger provinces, such as Ontario, under the pCPA, smaller provinces have presumably benefitted from much better prices than they could achieve on their own, thereby enabling them to cover drugs for their beneficiary populations they might not otherwise have been able to afford. While critics observe that the ability of provinces to opt out of a Letter of Intent detracts from the initiative’s negotiating power, its successes to date have also been seen by some as obviating the federal regulatory role in pricing.

4. Non transparent pricing

Because many countries have historically opted to regulate prices based on what manufacturers charge in other markets, a transparent price reduction in one market can drive prices down globally. In order to preserve their ability to price discriminate in the global market, manufacturers have adopted the practice of negotiating confidential discounts or rebates with payers which decrease the effective price of a drug without affecting its official list price. This practice has become so widespread that the World Bank has cautioned countries against relying on “best available” public list prices in other markets as a stand-alone method to control costs.Footnote 25

In Canada, PLAs between public payers and manufacturers, which provide for confidential, often volume-based discounts off the list price, are now the industry standard. Following a 2009 Federal Court decision Footnote 26, these confidential rebates are not reportable to the PMPRB for the purpose of determining compliance with its pricing guidelines and are thus not taken into account when the PMPRB sets ceiling prices for new patented drugs based on the cost in Canada of drugs in the same therapeutic class. Accordingly, private insurers and those who pay out of pocket must contend with list prices for new patented drugs that are not a true reflection of what is paid for existing therapies in the Canadian market.

5. Market segmentation/price discrimination

Although public payers have enjoyed some recent success in jointly negotiating price reductions from pharmaceutical manufacturers under the auspices of the pCPA, any resulting savings currently benefit the less than 35% of the market accounted for by the English-speaking provinces and territories.Footnote 27 Furthermore, residents of these provinces and territories who meet the eligibility requirements of their respective public plans do not see these savings reflected in lower co-payment amounts, as these are calculated based on the public list price, not the true discounted price, which remains confidential. This is the case both for pCPA derived discounts and those resulting from bilaterally negotiated PLAs, which flow back to government accounts in the form of year end rebates. While these rebates undoubtedly serve to alleviate some of the fiscal pressure on public payers, even the combined clout of the pCPA may not prevent a gradual scaling back in public coverage, in the form of stricter eligibility requirements or higher deductibles and co-pays, as Canada’s population ages and the expected wave of high cost drugs impacts the market. Indeed, with a generation of baby boomers now on the cusp of turning 65, some provinces have already migrated from age-based drug plans to income-based ones, as a pre-emptive cost saving measure.

Private insurers, who are responsible for about the same proportion of pharmaceutical spending in Canada as current participating governments of the pCPA, are no less impacted by these demographic and cost trends. The combination of greater prescription drug utilization by employees and their families, a rise in the number of high cost claimants and an increasing share in the subsidization of drug costs for retired employees occasioned by cutbacks in public coverage for seniors is resulting in less generous employer sponsored drug plans and less such plans in general. While this has obvious repercussions for the health and well-being of current and former employees and their families, it is also means a shrinking customer base for drug plan managers and the private insurance industry. In 2013, industry concern over these trends led CLHIA to release a paper calling for various reforms to prescription drug policy which it contends are necessary to ensure the future sustainability of drug coverage in Canada. Among the reforms sought by CLHIA are changes to the PMPRB’s legal framework which would see much lower price ceilings for patented drugs as a way of levelling the playing field somewhat between public and private payers.Footnote 28

Uninsured Canadians, such as the working poor in some provinces and small business owners, do not wield any negotiating power and tend to pay the highest prices of all, with one in 10 Canadians said to be unable to afford their prescriptions, according to a 2012 Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) study.

6. Debate over pharmacare

Heightened awareness of the challenges posed by many of the above described factors to the continued sustainability of the health system appears to have opened the door to a public conversation around the merits of a national pharmacare program. In the past year, there have been two separate academic treatises on this subject, both of which garnered significant media attention.

Gagnon (2014) Footnote 29 claims that implementing pharmacare would result in between $3 and $11 billion in savings through price reductions, systemic efficiencies, and the elimination of private drug plan administrative costs ($1.35 billion) and tax subsidies ($1.20 billion). Morgan et al., (2015)Footnote 30 make many of the same arguments and estimate the total public and private savings from pharmacare at $7.3 billion, and the cost of additional public spending of approximately $1 billion.Footnote 31

Pharmacare was also discussed at a meeting between provincial and territorial health Ministers and the federal Minister of Health in Banff in October 2014. Although no concrete commitments were made, provinces did agree to further intergovernmental dialogue on the issue, with Ontario’s Minister of Health, Dr. Eric Hoskins, volunteering to serve as the provincial emissary in pressing the case with the federal government.

Internal factors

7. Human resources

PMPRB Staff is composed of approximately 70 public servants in 11 different occupational groups. More than 35% of employees are over 50 years of age and at least 10 of them will be eligible to retire over the next 5 years. Since 2013, a number of senior PMPRB personnel left the organization or retired, including two directors, general counsel and managers in the scientific and price review groups. A succession planning report commissioned by the PMPRB in 2012-13, identified deficiencies in knowledge sharing and difficulty for more junior employees to envisage a career with the organization. Although previous feedback from staff suggested the lack of a sense of purpose and a lack of understanding as to how individual efforts serve to advance that purpose, the latest Public Service Employee Survey results show a marked improvement from 2011 on a number of related fronts. These include leadership and trust in senior management; communication of the organization’s vision, mission, and goals; strategic planning and program evaluation; and values and ethics.

8. Financial resources

In 2008-09, the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) approved an increase in funding for the PMPRB to help it to effectively deliver its mandate. This included a provision to increase the annual special purpose allotment (SPA) up to $3.1 million for hearing-related expenditures (reduced to $2.5 million as part of the Deficit Reduction Action Plan).

As a condition of receiving increased resources from TBS, the PMPRB agreed to conduct an evaluation of its programs in 2011-12, the goal of which was to assess the PMPRB’s relevance, efficiency and effectiveness, and the extent to which the increased resources helped it achieve its objectives. Overall the evaluation findings were positive and an action plan was implemented to respond to recommendations in the report on possible areas of improvement. At the same time, it is recognized that TBS’ decision to increase funding was based in part on the assumption that the number of hearings would increase substantially. To date, the PMPRB has not experienced the anticipated uptick in hearings, which has afforded it some flexibility to allocate its resources to expand and intensify its reporting activities. However, the annually renewable SPA monies remain earmarked exclusively for hearing related expenses.

9. The legal framework

The PMPRB operates within the enabling authority of the Act and the Patented Medicine Regulations (“Regulations”). The PMPRB has also issued the Compendium of Policies, Guidelines and Procedures (Compendium) to ensure that patentees are generally aware of the policies, guidelines and procedures pursuant to which Board Staff reviews the prices of patented drug products sold in Canada.

Unlike pricing and reimbursement authorities in many other developed countries, the PMPRB does not actually purchase drugs and thus lacks the buying power its counterparts exert when securing price concessions from manufacturers. Moreover, even as a ceiling price regulator, the PMPRB’s powers are not unlimited as the Act contemplates intervention where a drug price is considered “excessive” and offers only basic guidance as to what this means in practical terms.

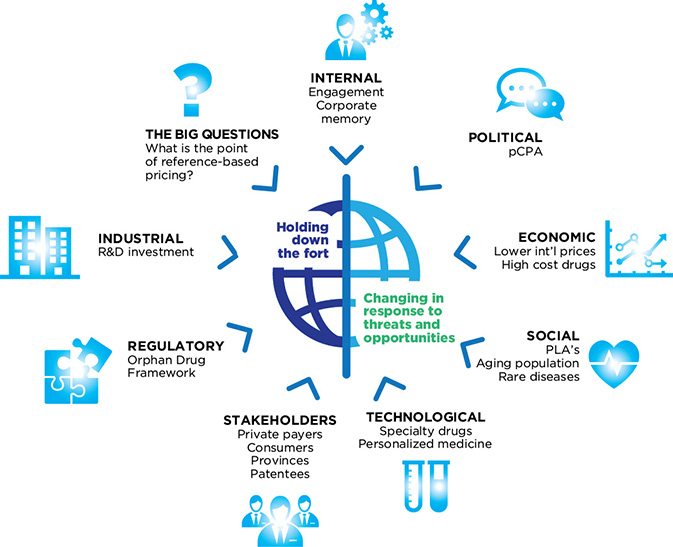

Figure 5: Environmental factors

Figure description

This diagram shows the relationship between the PMPRB and its complex external and internal environment. The PMPRB is represented in the centre of the diagram, and is described by the words “Holding down the fort” and “Changing in response to threats and opportunities.” The environmental factors affecting the PMPRB are placed around the perimeter of the diagram in a way that indicates a direct relationship between each factor and the PMPRB. These environmental factors are:

- Political

- pan Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA)

- Economic

- Lower international prices

- High-cost drugs

- Social

- Product Listing Agreements (PLAs)

- Aging population

- Rare diseases

- Technological

- Specialty drugs

- Personalized medicine

- Stakeholders

- Private paters

- Consumers

- Provinces

- Patentees

- Regulatory

- Industrial

- The Big Questions

- What is the point of reference-based pricing?

- Internal

- Engagement

- Corporate memory

c. SWOT Analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Threats, Opportunities)

Threats and opportunities

The steps taken by provinces and territories to pool their collective purchasing power under the pCPA in order to negotiate lower drug prices and obtain greater value for publicly funded drug programs raise legitimate questions about the continued value of PMPRB imposed price ceilings to provincial and territorial governments. Quebec's recently confirmed participation in the pCPA only adds to this line of inquiry. Footnote 32

The success of recent pricing and reimbursement reforms in other developed countries, and in particular the European members of the PMPRB7, constitutes a further threat to the PMPRB’s ability to ensure consistency between Canadian patented drug prices and international norms. Although Canadian prices remain slightly below median prices in the PMPRB7, this is solely due to the fact that US prices, which are much higher on average than all the other PMPRB7 countries, skew the median calculation.Footnote 33 Furthermore, if prices continue to decrease in Germany as a result of AMNOG, Canada will soon find itself second only to the US in prices, as was the case prior to the creation of the PMPRB in 1987. As it stands, of the many developed countries that engage in international price referencing, Canada is the only one to benchmark against US pricesFootnote 34, which can have an outlier effect on Canadian prices relative to European countries because of how the PMPRB’s current price ceilings operate.Footnote 35

Finally, there is a risk that the PMPRB’s price regulating authority will erode due to adverse judicial decisions on the appropriateness of its guidelines and the proper interpretation of the statutory factors in the Act—or their weighting— in determining the excessiveness of a price.

While all of the above pose a threat to the PMPRB in one sense, they also present opportunities.

In terms of the pCPA, the PMPRB has played a longstanding role supporting efforts under the Value Price Initiative to achieve significant reductions in generic drug prices. For several years, this consisted mainly of providing comparative data on generic drug prices in Canada relative to international prices. More recently, however, the PMPRB has been fielding an increasing number of requests from lead provinces in pCPA negotiations for international pricing information on patented brand drugs. Alberta’s recent adoption of the PMPRB’s CPI methodology as a way of regulating price increases for both patented and non-patented drugs in that province speaks to the closeness of this federal-provincial partnership, and there is opportunity for further such collaboration. Similar potential opportunities exist in the private market, as there is no independent government body that studies and reports on reimbursement and purchasing issues that are unique to private insurers and out-of-pocket payers.

Between 1969 and the late 1980s, a special compulsory licensing system for pharmaceuticals existed in Canada which permitted generic manufacturers to sell much cheaper versions of patented brand drugs at any point in the lifetime of the patent. Because of this system, Canada was criticized as a “free rider” on the R&D costs said to be borne by other developed countries where pharmaceutical patentees enjoyed the same exclusive rights as patentees in any other field of technology. The specific impetus behind the amendments to the Act that created the PMPRB and first scaled back, and then eliminated, compulsory licensing was the negotiation of a free trade agreement with the US and later the North American Free Trade Agreement. Through these amendments, Canada finally signalled its willingness to pay its “fair share” of international R&D costs.

From inception, the PMPRB has interpreted “fair share” to mean that Canadian prices, on average, should be in-line with prices in the seven countries set out in the Schedule portion of the Regulations. At the pre-publication stage of these regulations, policy makers initially proposed a more representative cross-section of 23 OECD countries for the Schedule; however, by the time of final publication, they opted for a more aspirational list in the sense that the selected countries had “R&D expenditures at levels that we (Canada) intend to emulate.” In other words, policy makers assumed that, by offering comparable pricing to these countries and full patent rights for pharmaceuticals, Canada would also come to “emulate” their R&D levels.

With Canadian prices now third highest of the PMPRB7 and Canadian R&D at a fraction of the PMPRB7 average (and falling), that assumption has clearly not been borne out with time. Given the national discussion taking place around pharmacare, concerns about drug plan sustainability in the face of a coming wave of high-cost drugs and calls for stronger price regulation in the private market, there is an opportunity for the PMPRB to look at possible reforms to its regulatory framework. Such reforms would be guided by a present day understanding of the underlying policy drivers, as described above, and current Government of Canada priorities.

PMPRB’s weaknesses

As a consumer protection agency, the PMPRB bears a weighty societal responsibility. Decisions by the Board in the exercise of its quasi-judicial function can have serious economic and reputational consequences for pharmaceutical patentees who are found in contravention of section 83 of the Act. Moreover, the PMPRB’s mandate requires it to reconcile seemingly conflicting public policy objectives, namely, access to patented drugs at prices payers can afford with the legitimate interest of pharmaceutical manufacturers in maximizing the value of their intellectual property. One might therefore expect conflict to be a routine occurrence and Board hearings to be commonplace. However, that is clearly not what policy makers envisaged in crafting the regime, given that the Board is composed of no more than five part time Governor-in-Council appointed members and thus has only so much capacity to conduct hearings. The upshot for the PMPRB is that it relies as much on moral suasion as the threat of regulatory enforcement in its dealings with industry, which may not be the most effective way of promoting compliance with pricing rules that, in theory at least, can be inimical to industry interests.

In order to function effectively as a regulator, a government authority must, at a minimum, have a complete and accurate picture of what the regulated party is earning from the sale of its products. However, the PMPRB is doubly handicapped in this respect in that neither the publicly available foreign price sources upon which it relies nor the information reported to it by patentees accounts for the confidential rebates and discounts which are now the norm both domestically and internationally in negotiated agreements between pharmaceutical manufacturers and insurers. While it can be argued that one benefit of this approach is an apples-to-apples comparison of domestic and international prices,Footnote 36 this is of little solace to private insurers and out of pocket payers in Canada, who pay substantially more than public payers in their own country partly as a result of artificially inflated price ceilings. If the PMPRB is to serve as an effective price regulator, it must adapt to modern day market realities such as PLAs.

PMPRB’s strengths

As a micro agency, the PMPRB boasts a small but agile workforce with a diverse range of skill sets and professional backgrounds. As such, it is well equipped to respond to the changes in its environment by adjusting its priorities from year to year in a manner that best serves its regulatory and reporting mandates.

Through the years, the PMPRB has relied on its reporting arm to cultivate a reputation as an honest broker and source of timely and impartial market intelligence for its stakeholders. The PMPRB has the expertise, financial resources and internal capacity to build on that reputation by broadening the issues on which it reports to appeal to a larger audience, particularly academia, private payers and consumers, and to elevate the profile of that work through a more proactive communications policy.

In terms of its regulatory mandate, the PMPRB can make more focused use of its SPA funding to pursue cases that have the potential to address aspects of its legal framework that will make it more effective in carrying out its mandate and that matter most to payers.

5. Strategic Planning

a. The process

Strategic planning is an organization's process of articulating its purpose, values and forward direction, and then making decisions on allocating resources to pursue this direction in furtherance of its purpose and in keeping with its values. The PMPRB’s strategic plan establishes multi-year objectives necessary to achieve the PMPRB’s mission and vision for delivering on its mandate. Annual priorities consistent with those objectives are set out in the PMPRB’s Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP) and the Departmental Performance Report (DPR) along with specific performance measures to assess how much progress is being made on each of the priorities from one year to the next.

The current strategic planning process began in December 2013, with a meeting between the newly appointed Executive Director and employees to discuss the results of the 2011 Public Service Employee Survey. At that meeting, the Executive Director committed to addressing concerns expressed by employees with respect to a lack of trust in management and inadequate employee consultation and communication regarding the PMPRB’s mandate and priorities.

In April 2014, the Executive Director and the rest of the management team presented the Board with a detailed scan of the PMPRB’s operating environment. In June 2014, the PMPRB retained an outside consultant to assist it in the strategic planning process. In October 2014, the PMPRB held a Town Hall to engage all employees on domestic and international issues impacting the organization’s work and obtain their feedback on a proposed vision, revised mission statement and potential new strategic objectives. In the months that followed, management and employees met to discuss specific initiatives and projects that could serve as a starting point for operationalizing the strategic objectives. These discussions eventually yielded comprehensive operational plans for each of the branches for 2015-16, the substance of which flows from the present document, which serves as a basic blueprint for the entire organization for the next three years. The present document was approved by the Chairperson, following the May 15, 2015 Board meeting.

b. Themes, vision and revised mission statement

Themes

The natural starting point to the implementation of new strategic objectives is the formulation of a new vision and mission statement. The PMPRB’s vision describes the ideal end-state the organization would like to see result from execution of the strategic plan. The mission statement describes what the organization aspires to be and what it does to achieve the vision. A properly formulated vision and mission statement should inspire staff and serve as a continuous reminder of the “why”, “what” and “how” of their work.

The PMPRB’s current mission statement dates from 1993 and consists mainly of a restatement of its regulatory and reporting mandates. Although the PMPRB has produced forward-looking documents in the past, to date it has not articulated an actual vision for the organization.

Three distinct themes informed the PMPRB’s thinking in developing the new strategic objectives: 1) Relevance; 2) Relationships, and 3) Renewal. These themes are to serve as touchstones for the organization as it moves forward with implementation of the strategic plan. “Relevance” speaks to the organization’s desire to overcome the threats in its environment and make a meaningful contribution to sustainable pharmaceutical spending in Canada, by protecting and empowering payers and consumers. “Relationships” recognizes that the PMPRB has a unique role to play in a complex and rapidly evolving regulatory environment and must build support for its vision and mission by developing strategic partnerships with public and private payers and consumers, as well as foster greater awareness of its role with the public at large. “Renewal” reflects a fundamental understanding that the PMPRB’s ability to deliver on the strategic plan depends on its ability to recruit, train and retain capable and engaged employees who support the vision and mission statement.

Vision

A sustainable pharmaceutical system where payers have the information they need to make smart reimbursement choices and Canadians have access to patented drugs at affordable prices.

Mission Statement

We are a respected public agency that makes a unique and valued contribution to sustainable spending on pharmaceuticals in Canada by:

- Providing stakeholders with price, cost and utilization information to help them make timely and knowledgeable drug pricing, purchasing and reimbursement decisions

- Acting as an effective check on the patent rights of pharmaceutical manufacturers through the responsible and efficient use of its consumer protection powers.

Motto

Protect, Empower, Adapt

6. Strategic Objectives for 2015 to 2018

Strategic objective 1: Consumer-focused regulation and reporting

When the current drug patent policy was enacted in 1987, the PMPRB was described as the “consumer protection pillar” of the amending legislation, Bill C-22. That description has been endorsed on multiple occasions by the courts, including by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2011, where it found that in interpreting its own regulatory framework, the PMPRB must take into paramount account its consumer protection mandate and its responsibility for ensuring that patentees do not abuse their statutory monopolies “to the financial detriment of Canadian patients and their insurers.”Footnote 37 In coming to that view, the Court was guided in large part by statements like the following from the sponsoring Minister of Bill C-22, the Honourable Harvie Andre, on second reading of the legislation in the House of Commons:

“I humbly submit that anybody who takes an objective view of what we are proposing will see that we have in place enormous checks and balances to ensure that consumer prices of drugs remain reasonable. They should look at what we will get by way of research and development, and at the jobs this will create.”

And a similar such statement by the sponsoring Minister of follow up legislation, Bill C-91, in 1992, the Honourable Pierre Blais:

“This legislation … is also a guarantee that Canadians can continue to buy patented drugs at a price that is and will remain reasonable.”

If the PMPRB is to remain true to that original policy intent at a time when Canadian patented drug prices are outpacing those in the PMPRB7 (with the exception of the US) and other European countries, R&D is at a record low and payers are struggling to cope with an influx of high cost drugs, it must adopt a more consumer-centric approach to how it carries out its regulatory and reporting functions. Footnote 38

In terms of the regulatory function, although it will continue to encourage voluntary compliance through a pragmatic application of its guidelines, in the coming years, Board Staff will focus its enforcement resources on cases that are most relevant to payers, and that raise issues which could clarify certain problematic aspects of the PMPRB’s regulatory framework and make it a more effective consumer champion. It will also examine options to bring more precision and policy coherence to its price ceiling setting process, with the objective of achieving affordable prices for all consumers.

In terms of its reporting function, the PMPRB will work with public and private payers to pursue opportunities for further collaboration, including putting systems in place which will facilitate and standardize the sharing of pricing, utilization and cost data so that insurers can make better informed and more timely decisions for the benefit of patients.

Strategic objective 2: Framework modernization

The Canadian regime has remained essentially unchanged since 1987, while the equivalent regimes in many other developed countries have undergone significant reform in order to address affordability issues, maximize value for money and keep pace with a rapidly evolving pharmaceutical market. In light of the above, the PMPRB will examine whether and to what extent changes to its regulatory framework are warranted if it is to ensure that Canadians pay their fair share for patented drugs, as was originally intended. In the short term, this entails examining options to modernize and simplify the Board’s guidelines, in keeping with the model of incremental change that has been employed since 1987. This examination will be informed by issues that emerge from the environmental scan, including but not limited to:

- Affordability

- Market power

- Price transparency

- Canada’s price gap with European PMPRB7 countries

- Price differentials between public and private payers

- Regulatory Burden

Longer term, the PMPRB will engage its federal, provincial and territorial partners in discussions on broader reform which would take into account international best practices, such as more integrated decision making on cost effectiveness, reimbursement and pricing.

Strategic objective 3: Strategic partnerships and public awareness

If the PMPRB is to succeed in its efforts to simplify and modernize its guidelines and bring broader reform to federal regulation and legislation, it must engage with a heterogeneous network of pharmaceutical industry stakeholders, each with its own unique interest and perspective on these changes. To do so effectively, the PMPRB must enhance awareness of its consumer protection mandate and build on its honest broker reputation with stakeholders and the public at large. It will do this through a fourfold approach. First, it will intensify its partnership with public payers to provide ever more timely and relevant market intelligence. Second, it will expand the scope of pharmaceutical topics on which it reports to provide private payers and consumers with information to help them make better, more cost effective choices. Third, it will work closely with international counterparts in sharing knowledge and best practices. Fourth and finally, it will adopt a more proactive approach to communicating its regulatory and reporting achievements to stakeholders and the public.

Strategic objective 4: Employee engagement

The PMPRB’s greatest asset is its people. To maintain standards of excellence and convince employees that the PMPRB is a desirable organization in which to build a career, it must attract, recruit, retain and rejuvenate a highly qualified, skilled, motivated and diverse workforce. To achieve this, the PMPRB will continue to inform and engage employees in the strategic planning process as it unfolds and annual priorities are developed and refined, and provide them clear direction on work objectives and expected behaviours in order to promote a culture of consistent high performance. It will also implement a comprehensive internal communications strategy to enable more structured dialogue between branches, management and employees, and to provide employees with regular opportunities to hear from a diverse array of experts on the big picture issues which impact our operational environment. Employees will be given the opportunity to provide their views on the degree to which their managers are meeting their engagement objectives and this feedback will inform year end performance ratings for executives.

The PMPRB will provide access to a wide range of learning and developmental opportunities and encourage junior officers to shadow their senior colleagues and gain exposure to the issues, challenges and situations that await them as they climb the organization’s ranks. It will seek out opportunities for its employees to pursue secondments or exchanges with other federal government organizations so that they can broaden their knowledge and understanding of the machinery of government. It will continue to add to its diverse skill set by hiring new employees from both inside and outside government with the experience and abilities to enable it to deliver on its other strategic objectives.

7. Conclusion

This strategic plan is intended as a high-level document to guide the implementation of the PMPRB’s strategic objectives through detailed operational and human resources plans. As a next step, the PMPRB will identify targets and deliverables to provide a link between the priorities specified in the Branch operational plans and the concrete steps that will be taken to deliver on them each year for the next three years. The PMPRB’s planning cycle will link human resources, business, financial and strategic planning more closely. While this strategic plan sets out a three year vision, the PMPRB will re-evaluate its priorities annually and adjust them as required to ensure that it continues to anticipate and respond to the emerging threats and opportunities in its environment. Having plotted our new course, we now set out to boldly follow it to a brighter future.